The stages of development of Tong Castle through the ages

This article forms part of Alan Wharton’s Report No. 4 on the Tong Castle excavation published in September 1986. The text and illustrations are not included in the Discovering Tong book.

Time travel menu

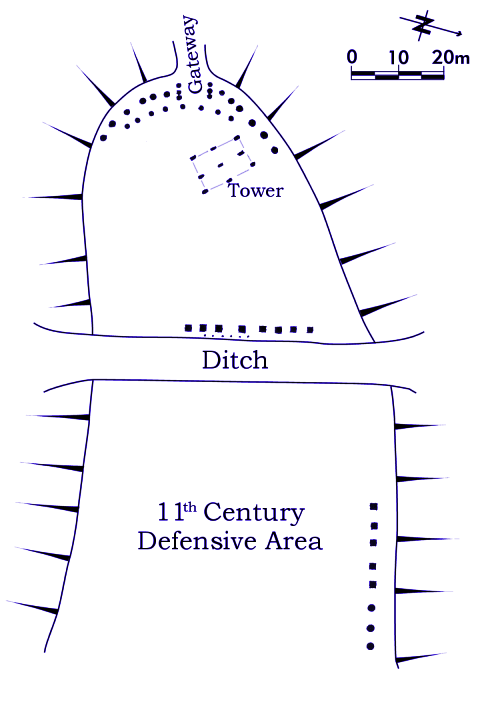

Tong Castle in the 11th century

The retention of the Manor of Tong by Earl Roger de Montgomery ➚, because of its fertile and well watered soil, would have led to the necessity to defend the Manor and look after its welfare without the Earl actually residing at Tong. A defended area on the natural rock promontory, the site of Tong Castle, would have been sufficient to give protection for his workers, families and their livestock against any marauding bands of warriors still marauding the countryside at that time.

Although it could still be called a ‘castle’, it has always been referred to as a ‘defensive area’, both on the excavation and in earlier reports, and so for the purpose of this Report it will retain the same description. The basic defences consisted of a continuous line of large timbers sunk into deep post holes cut into the natural rock around the promontory, with wicker breastwork between the timbers and a mixture of sand and stone built against the wicker breastwork to level out the surface to make a form of motte on the promontory.

There are, however, three phases of post holes on the promontory which could have been used during the construction of a defence at some time or other :-

1. An inner circle of small round post holes, approx. 25cm diameter, at the western end of the promontory.

2. An outer line of large round post holes, approx. 50cm diameter, at the western end of the promontory cutting into the smaller post holes especially in the gateway areas and they also occur at the north east corner of the site.

3. A line of large square post holes, approx. 75cm squares across the promontory and they also occur again at the north east corner but these could have been round post holes re-cut to a square shape as there are signs of re-cutting in more than one of them.

A further line of small stake holes, approx 10cm diameter ran parallel to, and on a cutting below, the line of large square post holes across the promontory.

The cutting of the small round post by the larger round ones, places these as an earlier timber structure on the promontory and the line of small stake holes could have been of the same period of use. An earlier use of the promontory than the medieval period would be quite in line with the finding of artefacts from the prehistoric to the Roman period in the surrounding areas, when the promontory could have been used as either a defensive or observation position.

If in fact the large square post holes are later than the large round post holes, it could suggest that an even larger area of the promontory had been enclosed by the line of timbers and whilst there was evidence in the machine cutting across the outer ditch of a shallow ditch cutting, it was so far out from the later line of the front curtain wall that any post holes in that area would have been removed by the deep outer ditch cutting. This would place a query as to why the line of large square post holes had been cut, sealing off the western area of the promontory, within the large enclosed defensive area.

Alternatively, the large square post holes could have been of the Norman period, such as at Abinger ➚ in Surrey and Quatford ➚ near Bridgnorth, with the large round post holes being of a pre-Norman period. The cutting of the ditch across the promontory, in line with the large square post holes would then have made the western are a more defensive area at that time. The possibility of a larger enclosed area whilst being in evidence from the north east post holes, must, at this time be the subject for further discussion only without further evidence.

A series of post holes for a building were cut into the natural sandstone to form a square and they were large enough to have enabled large timbers to be used and capable of supporting a two or three storied building. The upper part of the structure would have had a crenellated parapet to give greater freedom to defending archers than would a totally enclosed structure. Defending the area against weaponry of those times would have been relatively easy, with the lower part of the structure being used for accommodation or shelter.

The best known example of a similar such structure so far found, was at the excavation of the motte at Abinger in Surrey where there was a similar large timber enclosed area and a square watch tower structure. Although the motte at that site was constructed against a circle of large timbers, this being as practical a way of building a defensive area as using the top of the rock promontory, the defensive purpose was the same.

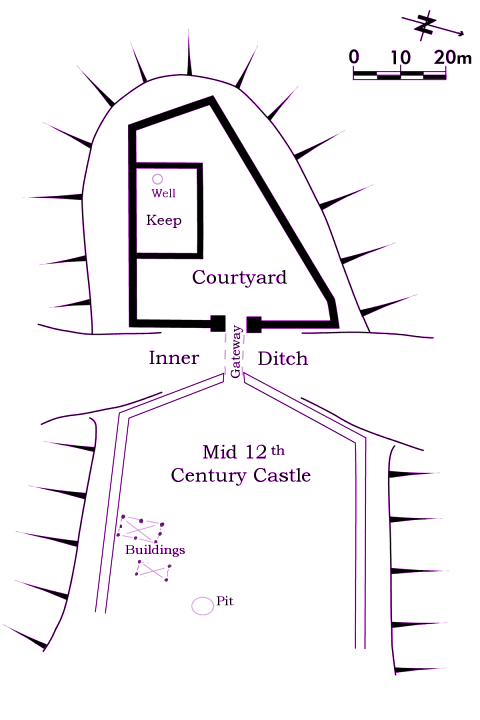

Tong Castle in the mid 12th century

At first the Norman castle at Tong was designed as a base for a small body of mounted soldiers and, under a single leader, it was possible to range over the area and in the event of an attack, the soldiers could return to a well protected base.

This base would contain a hall, kitchen, well, sleeping quarters and stables along with workshops for the smith and armourer and even perhaps a chapel. All were surrounded by a ditch outside a bank or rising slope. The entrance would be a bridge across the ditch to a gap in the bank and the gap would be further strengthened by a high timber fence. This constituted the bailey and the later addition of a watch tower gave added protection from attack outside and disturbance from within. For more safety and height, the tower was raised on a mound.

The earliest appearance of the true mound or motte is disputed and low mounds around the base of Roman towers have been found in Europe. However, the high motte appears in the late 11th century England and the motte top had its own fences or gangway against the slope. The size of the motte and bailey was mainly dictated by the need of the garrison and available resources, and such a motte and bailey castle was cheap and quick to build. Where a geographical feature was available, such as a rising hill or promontory, this was even a better place to build a castle as half the work in raising a ‘mound’ had been done.

A castle of permanent importance needed long-term buildings and defences, and its function was often as a centre of local government and the occasional residence of individuals of importance in the feudal world. Timber in contact with the soil rots quickly and therefore buildings would be raised on stone sleeper walls, either timber framed or of stone. The first such structure to be built of stone was often the tower.

The principal tower is usually called the Keep or Donjon and such a Keep provided the Lord of the castle with a place of privacy, safety and a prison for his captives, with a strong room for his treasures and documents. The Keep often held out after the rest of the castle had been overrun. A Keep would consist of three or four main rooms with small rooms built into the thick walls, and the rooms stacked vertically and the various floors would be linked only by a ladder or spiral staircase.

The arrangement was for the lowest floor to form a storage basement and often there was a well independent of that in the castle bailey. There was an entrance floor reached by an outside staircase of timber or stone with a gap in it crossed by a moveable bridge i.e. a drawbridge. The entrance door or series of doors would be strengthened and a form of lobby was frequently built to provide a landing or ancillary accommodation. Often the upper part of this fore-building formed the chapel. This or the next floor formed the hall for public business and above this was the private suite of the owner or his resident agent.

Walls were built above the roofs to protect them against missiles and a walkway behind the parapet was used for a lookout. A parapet on the inner side of the wall was called a parados, with a crenel or gap in a parapet. Slits were common near ground level, with the slits being used by archers to defend the Keep.

The inheritance of the Tong Estate by Phillip de Belmeis saw a great deal of ecclesiastical activity in Shropshire by the Lord of the Manor who, along with his brother Richard, founded the Abbey at Lilleshall as well as being a chief benefactor to Buildwas Abbey ➚ and accordingly would have required a suitable residence during this period in his Manor at Tong.

The reign of King Stephen ➚ saw the building of many castles in the county and Tong Castle was one of them. The sandstone built castle was inside the line of large timbers of the 11th century defensive area and was the first and possibly the only building in the site that could be classified as a castle. However, the biggest change to the site was the change of use from a communal to a private defence for the Lord of the Manor.

The Keep building and encompassing outer curtain wall was built of red sandstone excavated from an enlarged and deepened inner ditch which, with its vertical side on the western edge going down to a depth of 6 metres, and being some 8 to 10 metres wide, could be described as a perfect defensive ditch. There was evidence of the quarrying in the bottom of the ditch and this left the bottom uneven, presumably after having had sufficient sandstone removed for building.

The building of the curtain wall across the original entrance to the defensive area, moved the entrance to the now Keep area from the south and west to the east side and evidence from the ditch filling suggests a stone gateway with a timber bridge across the middle, and narrowest, part of the inner ditch. The curtain wall would have been a revetted dry stone wall sloping inwards and upwards on the outside, to some 3 to 4 metres high on the inside, with the top being of sufficient width to provide a walkway for the patrolling guards and a crenellated wall built on the outside for protection and defence.

The Keep building would have been at least two stories high to serve firstly as a watch tower, with its high vantage point, and secondly as a further means of defence and the flat-top roof of the building surrounded by a crenellated wall to provide protection for, and also help, the defending archers. The actual shape of the Keep Building was hard to ascertain from the excavations as apart from the south wall of the Keep building being part of the curtain wall, subsequent buildings in the same area destroyed most evidence of the foundations.

Evidence of burning in various areas within the Keep building suggests that all the fires and cooking were within the walls of the building itself. There would have had to be a well within the Keep area to complete its defensive role, but as to whether the later 14th century well had been a cleaned out, and re-cut 12th century well is still subject to much debate in the absence of locating any earlier well so far in the Keep area.

Excavation of post holes for two timber framed buildings in the area to the east of the ditch, the later front courtyard area, suggested their use as domestic shelter or accommodation and an adjacent rubbish pit produced artefacts dated as being of the mid-12th century.

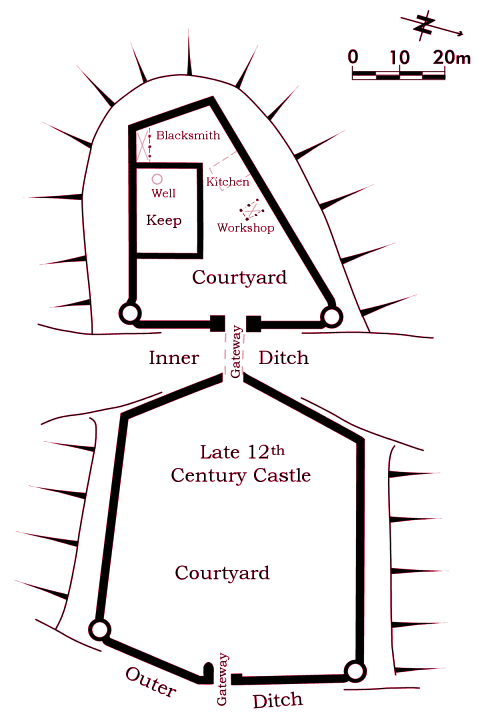

Tong Castle in the late 12th century

The marriage of Adelicia de Belmeis, heiress to the Tong Estate, to Alan la Zouche brought to Tong the powerful la Zouche family (whose lands included Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire) and with the addition of the Belmeis Estates not only saw the increase in the ecclesiastical grants to Lilleshall and Buildwas Abbeys ‘…accommodation in his (Alan la Zouche) wood at Tong Castle…’ but also the need for a larger castle in keeping with his newly acquired and more powerful status.

The enlarging and strengthening of the overall castle defences was achieved firstly by encompassing the front courtyard with a curtain wall, which necessitated the building of another gateway, secondly, the digging of another ditch across the promontory to protect the increased castle area, and, lastly, the building of round watch towers at the north east and south east corners of the Keep area and front courtyard.

Excavation of the outer ditch, especially in the gateway area, revealed a smaller ditch cutting within the later, and larger, outer ditch section, but was of insufficient depth to make it an effective defence in the terms previously discussed for that of an adequate defence. Whilst a wooden bridge would still have had to be used to cross even the shallow ditch, the new ‘D’ shaped Gateway would have provided adequate defence with the front courtyard being used presumably for communal use and the main defence still in the Keep area.

The excavation of a line of post-holes, inside the Curtain Wall and to the west of the Keep building, with heavily burnt areas from which came 12th century ironwork such as a spear and arrow-heads, suggests that it was used as a blacksmith’s workshop, a usual feature within castles of that period. The single line of post-holes pointed to their use as the main supports for a lean-to building against the curtain wall and possibly the end wall onto the Keep building.

Evidence of an early oven floor was located just outside the corner of the Keep building and being under the 13th century kitchen area, placed its period of use during the 12th century even though there were no artefacts to confirm this. Further post-holes for another timber framed building were excavated underneath the later courtyard building and from the heavily burnt sand layers, it could have been used for further industrial use or part of the Kitchen buildings.

Other pits and shallow slots, with a marl sealed sandstone rubble or gravel filling occurred within the Keep courtyard, but their dating, apart from generally being below the 13th century levels, could not be determined because of the lack of any artefacts from within the pits and slots.

Excavations in the demolished gateway area of the inner ditch, apart from locating the basic 12th century ditch cutting, also produced pottery and iron work similar to that found in the Keep area, on the top of the initial sterile sand layer, deposited immediately after the cutting of the bedrock from the inner ditch, which was from either the quarrying or erosion of the newly cut surfaces of the natural bedrock.

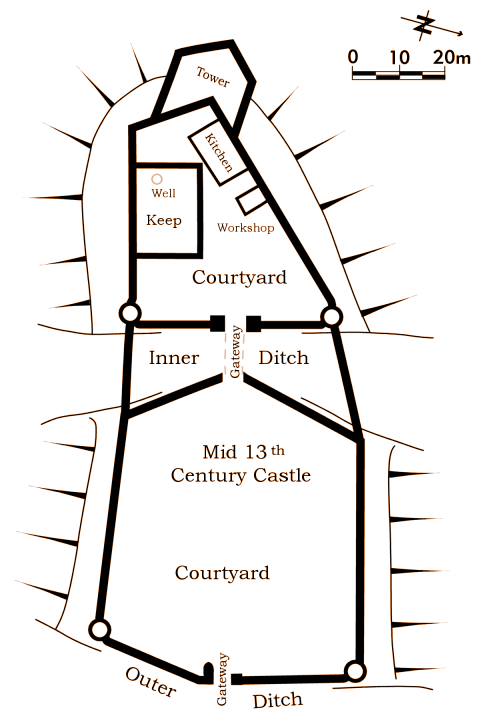

Tong Castle in the mid 13th century

Alan la Zouche, grandson of the first Alan la Zouche, succeeded to the Tong Estate and saw a relative period of stability, after the series of forfeitures of the estate to the Crown, which ended with Alan la Zouche paying all the outstanding fines in return for the estate being brought back into the family.

The 13th century in general saw the need for a more residential form of building whilst retaining the elements of the defensive nature of the original castle. This was achieved at Tong Castle by additions to the castle rather than that of a completely new building as so often happened during this period.

The building of the Angular Tower to the west of the Keep area, over the original entrance to the defensive area, increased the residential use of the castle and with this came the need for a substantial kitchen building with its numerous ovens and hearths to cater for the increased ‘household’. The original use of the Keep building must have continued into the 13th century as a small rubbish pit was located at the south east corner of the building.

A further smaller building in the Keep courtyard, with its heavily burnt cobbled flooring, suggested its use for some form of ‘industrial’ activity, and the heavily sooted sandstone and bronze fragments found amongst the building’s demolition rubble points to the use of the building for bronze smelting or working. The curtain wall was extended from the Keep area across the inner ditch to the front courtyard area on the north and south sides, and whilst still retaining a defensive role, it also totally enclosed the whole castle site.

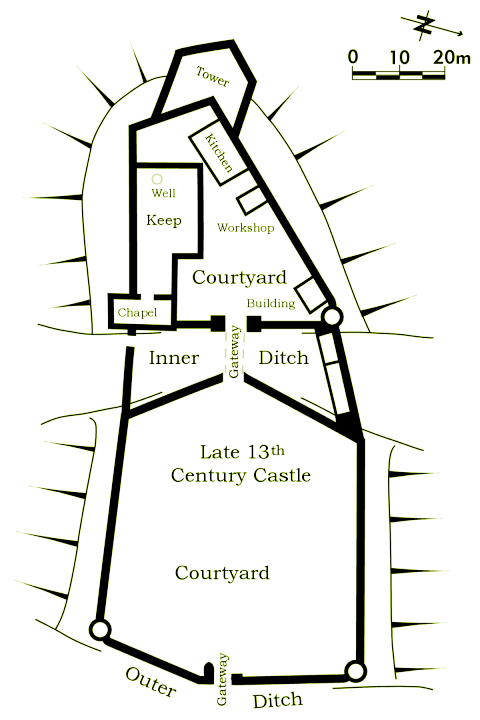

Tong Castle in the late 13th century

There was a further increased need for a more residential use of the castle as both the home for the Lord of the Manor and for entertaining visiting Courts and their entourage. This would have been necessary when, in July 1296, a fourth Inquisition sitting was held at Tong to decide as to who held the Manor of Tong, and this would have placed considerable demands on the buildings and the resources at Tong Castle in order to cope with the numbers of people involved in the holding of the sitting.

The curtain wall across the north end of the inner ditch was widened and strengthened so that a building could be built on top of the wall, with the east end being filled in to provide a rough buttress for supporting the end of the building. The building was presumably used to accommodate the number of attendant and the general domestic rubbish in the inner ditch fill from the building, and against the base of the building wall, reflected this occupation.

To erect the buttress building along the eastern edge of the inner ditch and onto the Keep building, necessitated the cutting through of the south inner ditch curtain wall, and from the evidence of the hearths against the inside of the curtain wall, it would suggest that the inner ditch at the south end was partly filled in at this stage. The ashlar faced stonework and the corner buttress especially along with stonework excavated from the inner ditch adjacent to the building shows the building architecturally to be of the c.1280 period.

Excavation along the Keep outer wall produced painted glass suggesting the use of the building as a chapel or for other religious purposes which would be in line with the architectural form. A further small stone building was located behind the north east round watch tower of the Keep area, but there was nothing to suggest its use and the artefacts were generally of the late 13th century.

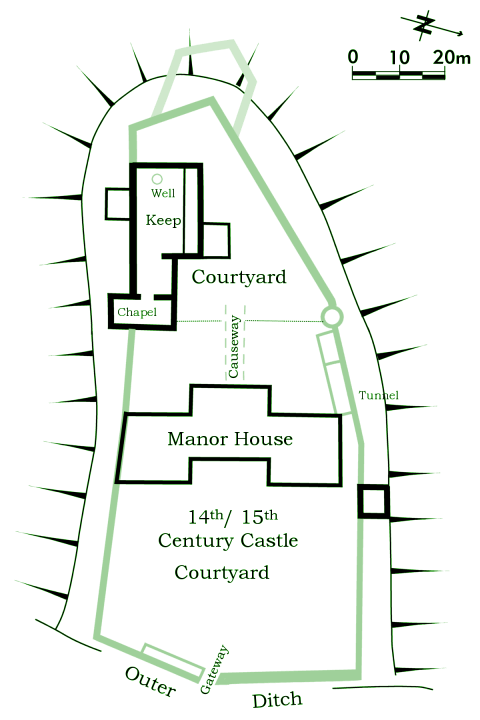

Tong Castle in the 14th and 15th centuries

The succession of the Pembrugge Family to the Tong Estate saw a period of relative tranquillity, and with the need for a defensive castle almost gone, the building of a Manor House of ashlar faced stone by Fulk de Pembrugge II was in keeping with other buildings of that time.

The remaining parts of the 12th century Castle would by this time had been in need of substantial repair, but the need to retain a fairly substantial ‘castle’ building and all its prestige, was still paramount. Evidence from the excavations showed a strengthening and deepening of the outside of the overall curtain wall and this was achieved firstly by the re-building of the outside of the wall, and secondly by the vertical cutting of the bedrock below the bottom of the wall.

The Keep building was further re-built and strengthened with the northern wall increased to 4 metres wide, which would have enabled small rooms to have been built inside the wall itself, with the upper floors having room for a passageway down the length of the building when the upper part was in use. Two Square Towers were built onto the Keep Building, at the south and north sides, with the angular tower possibly being demolished either then or earlier. A further square tower was built against the north east curtain wall by, and down from, the corner of the Manor house, with post hole cuttings inside possibly for a stairway.

The building of the Manor house in the front courtyard left the Keep building to be used as additional residential and domestic purposes and the need for a well either cut as new or an earlier one re-cut was necessary within the Keep Building. The advantages of cleaning out and re-cutting a well was the known factor that there was an obvious supply of clean water in that position and also, with the water source coming from within the promontory itself i.e. a water table, there would always be an adequate supply of water.

The ‘clean’ nature of the well fill suggested that the Keep was used for residential purposes only, but a level of burnt material in the well, along with extensive burning along the sides of the angular tower foundations, suggested that either the Keep building roof timbers or the tower roof itself had burnt down, destroying the timbers of both buildings, leaving the need for renovation. A new floor level had been laid inside the Keep building and in one corner, the base of a glazed storage jar was found on top of the new mortared floor level.

The Buttress building was then used as chapel, with the Lichfield diocesan records confirming the attendance of a Priest for services to the Lord of the Manor at Tong. The Inner ditch had by that time been nearly filled with the demolition from earlier castle buildings, and a causeway was built on top of the demolished gateway stone work for a better access to the Keep area.

At the time of the Peasants’ uprising ➚ in c.1381, Fulk de Pembrugge IV was granted a licence to crenellate the castle, and as result the outer ditch was widened and deepened from the front gateway outwards and an impressive, if not actually defensive, gateway was built about the earlier gateway.

Although the outer cart of the outer ditch was deepened, with the stone possibly used for building purposes, the depth of the ditch at the gateway remained the same, with the ditch sloping down and outwards from the centre.

During the excavation of the tunnels and cellars under the later castle buildings in the front courtyard area, ashlar faced sections of tunnels were located in the cellar on the north side. On the south sides at the top of the stairway from the wine cellar, the remains of a set of timber slots were found cut into the ashlar faced side wall, but with the many later cuttings for the tunnels and cellars, it was impossible to explain their function in the 14th century.

Excavation of the foundations of the castle buildings, whilst they were substantial in themselves, where they were built on top of earlier castle foundations they were not of a substantial nature and this could have led to an earlier than usual dereliction and this could have been the reason for the following Grant being given after the death of Isabel de Pembrugge in c.1446.

26 Henry V – Calender of Charter Rolls – Number 2: Membrane 2

Grant, of special grace, to the Warden and Fellows of the College of Saint Bartholomew, Tonge, in Shropshire and to Richard Vernon, king’s knight, and his heirs, of the following :

they shall have all goods and chattels called ‘stray’ and all goods and chattels called ‘wayf’ and all treasure trove in the castle and lordship of Tonge, and the goods and chattels called ‘manuopera’ taken with any person therein and disavowed by the person before any judge;

they shall have the goods and chattels of all their men, tenants, and residents therein, being felons, fugitive, outlawed, waived, condemned, adjudged, attainted, abjured, convicted and suicides, and also all confiscated goods and chattels found within the said castle, in the usual form, with the usual power to put themselves in seizing thereof, without impediment, even though the said goods and chattels had already been seized by the king and his ministers;

they shall have returns of all assizes, plaints, attants, writs, precepts, mandates and bills of the king’s and executions of the same by their bailiffs within the said castle and lordship………………..

they may appoint justices to keep the peace within the said castle and lordship and of craftsmen and labourers there, and change and remove such justices……….

with clause ‘licet’, and not withstanding that there is here no express mention ect.

Held at Westminster June 6th – 1448

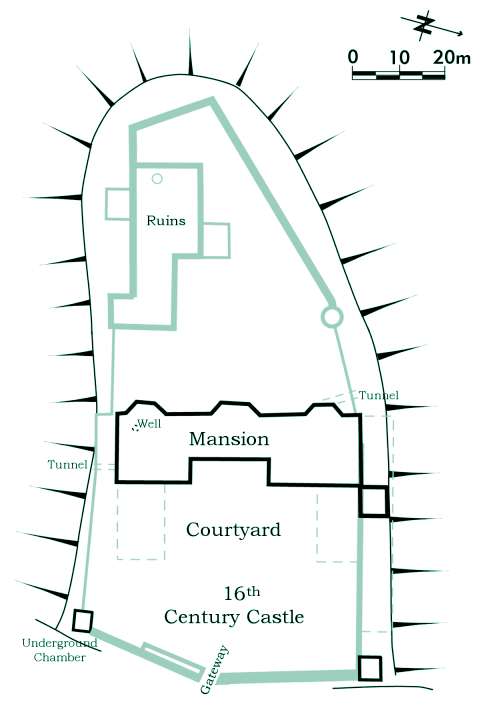

Tong Castle in the 16th century

The inheritance of the Tong Estate by the Vernon Family of Haddon ➚ in the Peak District with their many Royal connections, brought the need for a more palatial style of building at Tong to replace the then almost derelict medieval Manor House. A Tudor styled Mansion, with two wings and a joining Hall, was built of brick similar to the same design as Hampton Court.

The new Mansion was built generally over the foundations of the Manor House and with the need for any form of defence now gone, the new, fashionable brickwork, made to reproduce all the facets of carved sandstone, brought about a complete change in architecture and was the start of the use of the ‘castle’ at Tong to entertain guests, rather than as a seat of power for the Lord of the Manor.

The use of brick was total and in places, where the medieval sandstone foundations were found to be inadequate, strong brick piers were constructed to take place of the earlier ones. Although the bricks were hand made and soft fired, the strong mortar bonding produced a structure as strong as, if not stronger than the sandstone blocks. New square Towers were also built of brick at the south east and north east corners of the front courtyard.

At the bottom of the south east tower, a chamber was built with a brick arched roof support, and extending from the Tower, and along the edge of the outer ditch a high wall was constructed making the chamber ‘invisible’ from outside the ditch. Entrance to the chamber was through an inward opening door and in one corner was a ‘squint’ slot to look down, but not to be seen from, the south outer wall, making it a very hidden and secluded place.

With the earlier tunnels underneath the old Manor House being either extended or re-built, it became possible to traverse the length of the building underground without being observed and it would therefore have been possible to hide in the underground chamber, move along the high south outer wall and then into the Tunnel entrance and onto the diagonally opposite area of the Mansion if necessary and many uses can be thought to utilise this facility.

Alongside the entrance to the tunnel on the south, a rubbish chute pit was located, with the chute having been built down the outside of the Mansion for the disposal of rubbish. The pit would have been cleaned out periodically, but inside the pit was the last deposit which was of a domestic/kitchen content.

Although the well in the Keep building would still then be open, demolition and other rubbish would have made it unusable and a new well was cut into the natural bedrock down to a depth of about 5 metres to locate the water table.

An area to the north west corner of the courtyard had small buildings surrounded by a cobbled courtyard which looked like a stabling area for the Mansion. Below the cobbled area to the north was built about, and below, another square tower on the medieval watch tower foundations along with a series of domestic type buildings, presumably for the kitchens etc. and these were generally below the Mansion.

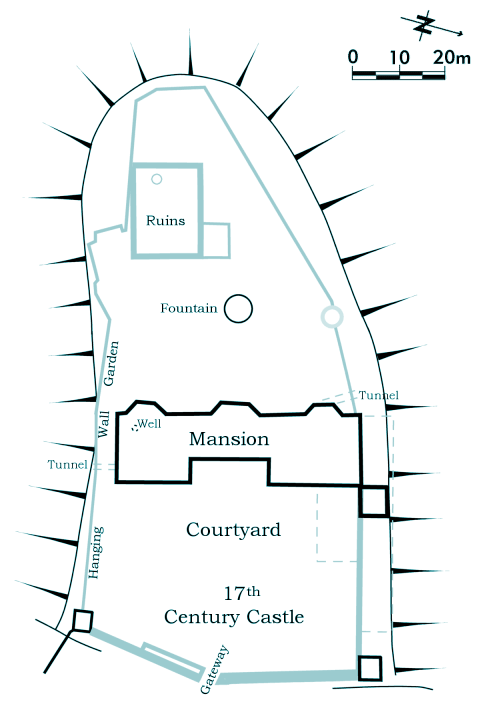

Tong Castle in the mid 17th century

The period of stability during the Lordship of the Vernon Family at Tong, lasted until the outbreak of the Civil War by which time the Manor of Tong had passed to the Hon. William Pierrepont of Thoresby ➚ in Lincolnshire, where he spent all his time during the hostilities. Being a Parliamentarian landowner in a basically Royalist stronghold, resulted in the 16th century Mansion being used for prestigious, rather than practical purposes and accordingly was the centre of two sieges at Tong.

Further, with William Pierrepont being on the Committee of Safety he would have had some measure of influence as to what actually happened to the Mansion during the Civil War ➚ sieges but the only obvious damage was recorded as that to the east Wing and the surrounding buildings. The damage was repaired or rebuilt using a mixture of brickwork and yellow sandstone in a rusticated design of the 17th century.

The main excavated area that showed the extent of the damage was at the lower part of the south east tower and the Underground Chamber, where the tower itself had been demolished and the chamber rebuilt, using brick and sandstone, to the same style as the original, including the ‘squint’ hole. However, from the material found in the chamber itself it had obviously been used as part of the gardens with plant pot remains and a water trough for dogs found outside the door and a summer house built above the chamber.

The original medieval outer Curtain Wall in the Keep area was ‘straightened’ out and used to form part of a Hanging Garden, with a less substantial sandstone wall built in areas where the Curtain Wall had been removed completely, having a gravel pathway laid on top of the wall, bordered by sandstone balustrading, with a protruding balcony from which the guests could ‘view’ the entire length of the south hanging wall garden.

The Keep building and other areas in the Keep were levelled and the excess material put into the remains of the Inner Ditch to finally level it, and a water Fountain was constructed on the edge of the Inner Ditch. The Keep building foundations were re-laid in outline form to turn the ‘ruins’ into a garden feature and a large pit located and excavated in the Keep courtyard had burnt limestone and copper nails in its fill presumably used during the Keep landscaping.

A further large pit was excavated within the front courtyard, in the approximate position of where the East Wing would have been, but apart from material of the Civil War period being in the pit, it had no obvious use. There was however, no trace of the demolished East Wing inside the wall foundations and this could only be put down to the extensive levelling, even in the Front Courtyard, where the Gateway foundations had been landscaped as a ruin.

The water fountain and hanging garden were part of an overall garden landscaping about the Castle, and the construction of a pool around the promontory to the west, with a gravel trackway below the outer walls from which to walk along the edge of the pool which, along with the Italian style garden to the east of the Mansion, completed the new style of landscaping for the period.

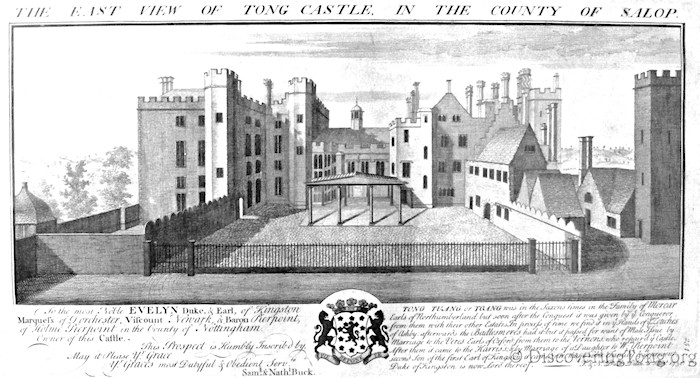

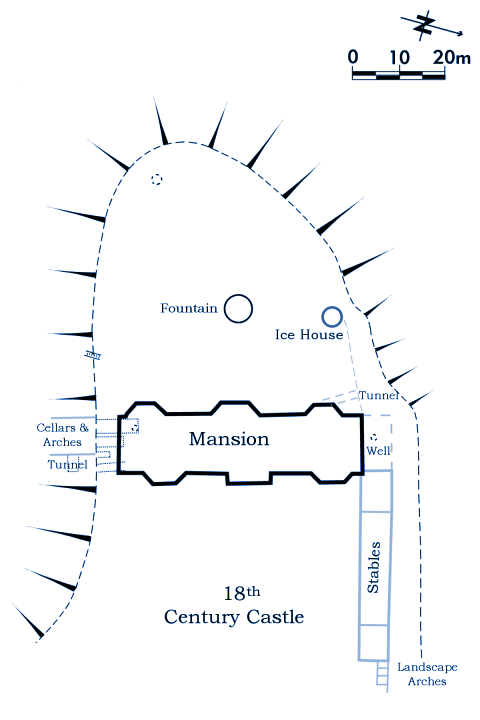

Tong Castle in the 18th and 19th centuries

The last Castle or Mansion was built by George Durant, after he bought the Tong Estate from the Pierrepont Family, and along with Lancelot [Capability] Brown ➚, he not only built a building far removed from any others that had earlier been built on the site, but also removed all the traces of the buildings by an overall landscaping emanating from, and about, the new Mansion to eventually encompass Tong itself whilst still retaining the rural look of the area.

The Mansion, variously described as a Country House, a Castle and a Turkish Bath, was built about the foundations of the 16th Century Castle, but the new and more extensive Cellars added more underground passageways, which demolished or cut through most of the earlier foundations. Excavation of the new foundations, which had been built, found them to be of a very insubstantial nature and incapable of supporting the ornate sandstone building for any lengthy period of time.

A Surveyor’s report in c.1855, less than 100 years later, recommended that the building should be demolished because it was not fit for habitation. Although the demolition did not finally happen till 1954, when the Mansion was in almost complete ruins, the northern part was lived in up to the First World War, with the rest of the Mansion sealed off for safety reasons.

Although the earlier buildings had been levelled off and covered over by up to a metre of soil and rubble, that did not stop the use of the steep medieval outer walling in the landscaping such as on the south side where a huge Wine Cellar was cut through the wall and bedrock and into the earlier Well, which was found filled in, and the Wine Cellar was reputed to be capable of storing up to 360 dozen bottles of the finest Wines, with a staircase for access to the Mansion.

Along from the Wine cellar was a smaller Cellar which had a boiling oven and other structures suggesting its use for brewing and the bottling of beer. Between this Cellar and the entrance to the Tunnel were Landscape Arches, used to extend the ground around the Mansion over the steep walling, and these were used as storage places for gardeners and servants. One of these arches had the pit for the 16th century rubbish chute under its floor, and at right angles to the arches was a further arch, used firstly to extend the landscaping, and secondly, as a boat house for the South Pool.

The entrance to the Tunnel and Cellars made the south side accessible to all the servants working there and provided a useful means of movement along the length of the Mansion underground and out of sight of guests and the Mansion.

The Cellars and Tunnels beneath the Mansion provided a network of access points into the Mansion itself, without the servants and staff having to actually walk about the Ground Floor for other than serving the Lord of the Manor and his guests. Although all the Cellars could not be completely cleared of demolition rubble during the excavation, the main Larders and Cellars were cleared at the north end of the building to enable a general layout to be seen.

The last ‘Cellar’ was in fact the Servants’ Room and had a Fireplace in the inside wall, through which was the entrance to the Tunnel, and in the opposite wall a doorway led to a stairway down to the Stables. The Stables were built against, and below, the steep outer medieval Curtain Wall and a separate inside wall had been built against, and keyed to, the earlier walling. On demolition of the inside wall, damage by Cannon Balls fired at the castle during the sieges of the Civil War was revealed.

Stables were built underneath the steep walling to increase the depth of building and so make them ‘invisible’ from the Mansion, the floor was cut into the natural bedrock with the drainage channels cut down further and covered by sand and cobbles for the Stable floor. At the end of the Stable building, further Landscape Arches had been built to fill-in the end of the deep Outer Ditch and these had been used to store Horse Carriages with a Blacksmith’s Workshop in one Arch and a cobbled Driveway alongside the Arches, Stables and Church Pool.

Also from the Servants’ Room, a Spiral Staircase went through the 16th century brick foundations and up to the front of the Mansion, with a hinged iron cover to hide the entrance. Next to the Servants’ Room to the west were two further rooms; in the first was a Well which had been cut down to a depth of 9 metres through, and into, another of the promontory’s water tables. The Well had been covered later by iron plates on which had been mounted a hand pump, which had been used to draw the water from the Well.

At the back of the Well Room, a blocked-up Tunnel arch was found but this had been sealed off during the building of the Cellars. In the west wall a short stairway went down into a room, along the back of which a ‘table’ had been built of re-used ornate yellow sandstone to produce a cool-slab. In the end wall a further stairway went down to the lower Stable level, going alongside an arched cellar which support the Cooling Room floor. Apart from some burning at the back of the Cellar it could be assumed that it had been used for storage.

Next to the cellar was a further Landscape Arch which partly supported the entrance to the Tunnel from the north side. From the northern Tunnel entrance a trackway went through an overhanging passage to the Ice-house. During the excavation and removal of the Ice-house to the Avoncroft Museum of Buildings ➚ site, it was found to have been built inside the foundations or cellar of the 12th century Round Watch Tower at the north east corner of the Keep courtyard area. The Ice-house had iron rails across the top for an open floor level for storage of game.

A new Fountain was built over the 17th century one, into the West Lawn, with water from a Ram Pump in the Church Pool Dam providing pressure for a high jet of water from the centre of the Fountain providing an impressive west view from the Mansion down the lawn. Steps from the lawn to the south-west down to a path leading to the boat house and the South Pool. The construction of the South Pool, to the south and west of the Mansion, and the North or Church Pool, sweeping from the Stables onto and beyond the Tong Church, would have provided an awe inspiring view for the guests arriving down the wide gravel drive along the front lawn to the front of the Mansion.

This page: Copyright © 2007 through 2022 Discovering Tong

To find out more about Tong please buy a copy of the Discovering Tong book;

the profits from the sale of the book go towards maintaining Tong Church.

Would You Like To Support Us?

The Tong Vision for 2020 and beyond has a target to raise £500,000 over the next 3 years in order to fund urgent and

essential restoration work, and to ensure that all visitors and congregations can continue to enjoy this unique building!

If you can offer your support either financially, in-kind or otherwise, please contact us or visit our JustGiving page by clicking the image, below.

A big thank you to all our supporters! Particular thanks go to the following:

To view details of our charitable status please click here