St Bartholomew’s, Tong

Discovering Tong

St Bartholomew’s, Tong

Discovering Tong: Its History, Myths and Curiosities

by Robert Jeffery

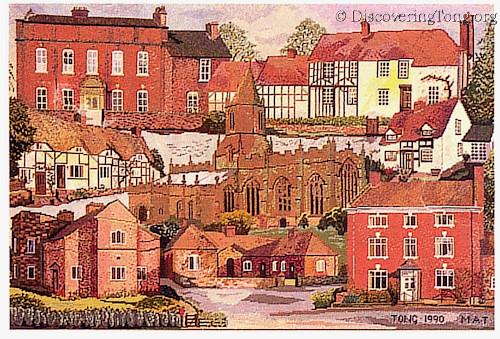

The small village of Tong possesses an immensely rich historical and cultural heritage. Discovering Tong is a book which explores many aspects of Tong’s heritage during the past one thousand years. It will particularly appeal to those acquainted with Tong, providing additional insights into the concept of ‘place’ and the processes by which a sense of identity is formed and sustained by a community.

Drawing on various resources – oral tradition, published material as well as local and national archives – the author builds up a detailed picture of the village of Tong and its institutions. Topics include the owners of Tong from 1066-1954, among them, families who played a significant part in English History; the history of Tong College; the 15th century Church of St Bartholomew the astonishing exploits of the Durant family, who came from Worcestershire and owned Tong from 1764-1854; the life, occupations and recreations of the inhabitants; records of the post-Reformation clergy and Tong’s surprising literary connections including Shakespeare and Dickens. The book contains a large number of illustrations some of which have not been seen before and some that have been specially commissioned.

While Vicar of Tong and Archdeacon of Salop, Robert Jeffery became aware of the power of Tong’s past and has used his retirement to document this. Following Tong, he became Dean of Worcester Cathedral and then Sub-Dean of Christ Church Oxford.

In his Foreword, the late Very Revd Dr Alan Webster\, KCVO\, Dean Emeritus of St Paul’s ➚, describes the author as “a faithful priest and honest historian” whose “reflections on Tong, a single community, surviving civil war and major religious and cultural changes are a spur in our days of terrorism to reflect on our society’s future and our need for radical alignments and local resilience”.

Note: all the profits of the sale of the book will go towards the maintenance of the fabric of Tong Church.

Book Reviews

“The book tells us much about English life… and reaches beyond Shropshire. The author concludes that to research the history of a place is not only a historical exercise but a theological one.” Church Times

“This book is in a distinct literary tradition – the delightful and authoritative account of his parish by a long serving clergyman. Think Gilbert White of Selbourne but add architecture.” Journal of the Ancient Monuments Society

“Forget the Archers and the disgraceful little Ruarie. Compared to Tong, Ambridge is semi- monastic. Robert Jeffery has written a history of his old Shropshire parish and it’s sensational. George Durant II, squire in the early 19th century, was ‘reputed to have a child in every cottage on the Tong estate.’ When the details – housemaid seductions, simple homely family hatreds follow, they put the water-colourist’s England into pallid perspective. This is a quite brilliant book, 200 pages of minute research showing a county family auditioning for left wing propaganda.” Edward Pearce in Tribune Magazine

“The castle was blown up by the army, Shakespeare wrote an inscription in the church and Little Nell is buried there. It’s the weird and wonderful and sometimes mythical world of the Village of Tong as uncovered in a new history by a former vicar.” Shropshire Star

“The book is in the grand tradition of quality local histories – objectively related with love – and contains not a few excellent illustrations by the author’s daughter.” Journal of the Methodist Historical Society

To find out more about Tong please buy a copy of the Discovering Tong book; the profits from the sale of the book go towards maintaining Tong Church.

Discovering Tong is a book which tells the stories about a village in rural England. It brings together all the known historical information about Tong, Salop some of which has only recently become available. The book has 54 illustrations, several are reproduced for the first time (including 6 in colour and 3 maps). The book is the most comprehensive book on the subject in the last hundred years. It comprises the following chapters, click on the heading link for more information about each section.

Foreword by the late Very Revd Dr Alan Webster, KCVO, Dean Emeritus of St Paul’s.

Prologue introduces the author, the Very Revd Dr Robert Jeffery, Dean Emeritus of Worcester and former vicar of Tong.

Chapter 1. The Story of Tong

Visitors to Tong, Shropshire over the centuries have been delighted when they discover this small rural village and in particular its fine fifteenth century church. Tong has many stories to tell, both the true and the fabricated, the book examines many of them.

The first chapter of the book acquaints us with the location of Tong and recounts some of the impressions of visitors including Elihu Burritt ➚; Revd R. W. Eyton ➚; John Betjeman ➚ and Simon Jenkins ➚.

“Tong Church! Did one in five hundred of all the Americans who have visited Haddon Hall in Derbyshire ever visit this little Westminster of the Vernons? It is doubtful. It is even possible that I am the first and only American who ever saw it. Even a man well read in the general history of the country will be astonished on entering this miniature cathedral, for such it is and looks in its interior and exterior aspects. In the first place, it is doubtful if any other village or provincial church in England contains within its walls so many beautiful and costly monuments to the memory of so many noble families as this little Westminster. You see here how and when these various families intersected with each other in wedlock and inter-weaved the new branches they put forth as a result of the union. Here you may read their histories, their graces and virtues, if you can decipher monumental Latin.” Elihu Burritt 1868

“Despite a motorway nearby, the church on its mound seems to exist in a time of its own. The little village gives plenty of signs of a dignified past, fallen into disuse but not much overlaid.” Robert Harbison 2006

“If there be any place in Shropshire calculated alike to impress the moralist, to instruct the antiquary and interest the historian that place is Tong. It was for centuries the abode or heritage of men great either for their wisdom or their virtue, eminent from their station or their misfortunes. The retrospect of their annals alternates between the Palace and the Feudal Castle, between the Halls of Westminster and the Council-Chamber of Princes, between the battlefield, the dungeon and the grave. ” Revd R. W. Eyton 1854

Chapter 2. Tong Castle

The early history of Tong, Salop (1066-1760) is dominated by the Castle and the Lords of the Manor who owned the land. Tong Castle stood in the village for nine hundred years, controlling the community and providing employment for the villagers. As the eminence of the Castle owners ebbed and flowed so did the fortunes of the village.

“Over time the prosperity of the manor increased. As the population grew, these defences were, by stages, strengthened and extended; using stone instead of wood, to keep pace with the advances in the techniques of warfare. From the 12th century, most English castles were built or rebuilt in stone.”

Chapter 2 documents the lives of the early owners of Tong up to the middle of the eighteenth century. It includes a number of family trees that show how the ownership of Tong passed amongst the leading land-owning families of the time. These include the Montgomery – Earls of Shrewsbury ➚ ; de Belmeis family ➚; la Zouche family ➚; de Harcourt ➚ families. It was the Pembrugge family who made Tong Castle more of a home than a fortified castle. They had a major impact on the village by building the present Church and founding Tong College.

Ownership passed by marriage into the rich and prominent Vernon family ➚ followed by the Stanleys ➚ (Earls of Derby). During the time of Sir Henry Vernon ➚, Tong was at its height of national importance as the Vernon family prospered under Henry VII ➚ (the Vernons had fought for Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth ➚). See also: Sir Richard Vernon; Henry Vernon; Sir William Vernon; .

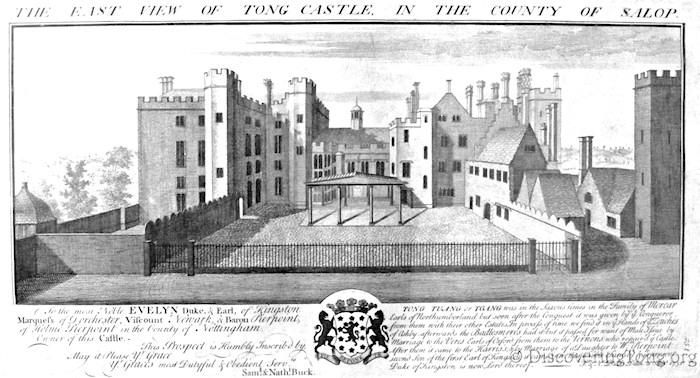

Excavations of Tong Castle in the last 30 years have shown a very complex sequence of building and re-building confirming the Buck engraving as a fair representation of the Castle at the time.

“Prince Arthur spent time with Henry Vernon at Haddon Hall; where there is a room known as ‘The Prince’s Room’. His tutor would have been there with him. One tutor was Arthur Vernon, son of Henry, who later became Rector of Whitchurch. The Prince had several tutors. The principal tutor, appointed in 1496, was Bernard Andreas. (He was also Poet Laureate). Andreas was an Oxford graduate who was introduced to Henry VII by Bishop Fox of Winchester (1401-29).

Prince Arthur ➚ moved to Ludlow Castle in 1501 and Henry Vernon witnessed the marriage contract of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon ➚. The marriage took place in St Paul’s Cathedral on 14th November 1501.”

When Tong was sold in 1603 to Sir Thomas Harries ➚ the country was in the troubled times of the Reformation and then the Civil War. Ownership passed on by marriage to the Pierreponts ➚ (Dukes of Kingston). William Pierrepont (William the Wise) was a trusted negotiator between King Charles I and Parliament after the ‘Second Civil War’ of 1648.

“William’s home was Holme Pierrepont at Thoresby ➚ in Nottinghamshire. He chose to remain there during the Civil War, and was buried there. Tong Castle was involved in two sieges during the hostilities between the Royalist and Parliamentarian sides. There was some damage to the east wing of the Castle, as well as to the Church. Afterwards, William Pierrepont arranged for repairs to be carried out, and made other alterations, (including the creation of a hanging garden). The remains of the old keep were levelled and landscaped. New features included a fountain in a pool along the western promontory, and an Italianate garden to the east of the house.”

Tong became a distant outpost of their estate and not a permanent residence. It was not until 1764 when George Durant bought the Manor of Tong that any great change took place.

Late fourteenth century pewter cruet unearthed during the excavation of Tong Castle.

Chapter 3. George Durant comes to Tong

George Durant’s Castle at Tong.

By the mid-eighteenth century the mediaeval concept of Lords of the Manor changed. No longer was the importance of the village rooted solely in agricultural land and a tight knit group of feudal families. The increasing prosperity of England gave rise to a new order of gentry with abundant money to bestow upon their estates.

The village of Tong in Shropshire exemplifies this trend in as stark a fashion as possible. George Durant, who made it rich in the West Indies, bought the estate from the Duke of Kingston and made his mark by rebuilding the Castle in a grand and bizarre style.

Chapter 3 includes newly available material to shows how George Durant came to his fortune and how it was spent at Tong.

George Durant led a remarkable life, as a young man he became infatuated with Elizabeth Lyttleton the second wife of George Lyttleton ➚, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The scandal was noted by his brother in a letter:

“This affair has now got wind and all town talk of it; report you may suppose has exaggerated the circumstances and ’tis generally said her ladyship was caught abed with the young man…her infernal temper has left her so few friends that I don’t hear of a single person who speaks in her favour, or that abuses Sir George or his family for the part he has taken. On the contrary, his enemies ascribe great merit to him for his behaviour in this delicate business.”

To escape the scandal George Durant was dispatched as Paymaster to the British troops in the expedition to Guadeloupe. From his diaries we read vivid accounts of the Battle of Guadeloupe ➚ (1758) :

“He reported that in the engagement, 150 troops were killed, and 200 wounded. He was appalled at the destruction, and when he landed, two days later, the whole town was deserted. The pavements were hot from burning sugar and liquor.

He went into a church, not as badly destroyed as the other buildings. The description is vivid: ‘It was covered with Rubbish & left in the utmost Disorder. The isles were full of Trophies & relicks, the pews were every where scattered with beads and Books; the vestries on each side of the Chancel were a foot deep in papers, prayer Books, Musick, was lights, massive Candlsticks & ten thousand nameless trinkets & all within the communion rails was crowded with those gaudy trifles which are held most sacred; so it was impossible to stir a Step without trampling on the Blessed Virgin Mary or kicking before you a wooden apostle or a maimed crucified Jesus.’”

On his return trip to the Indies in 1762 he took part in the Battle of Havana ➚, George Durant amassed a large personal fortune.

“The city capitulated on 14th August, and a large amount of booty was taken. It was from this venture that George Durant returned a very rich man with over £300,000. (The equivalent today would be around £15 million)”

The purchase of Tong was subject to considerable negotiation and haggling. George Durant despite his fortune drove down the purchase price, commenting on the poor state of Tong Castle he writes:

“‘The Castle and the grounds are in a miserable state of repair. The rain is coming in through the leads and in need of re-roofing.’

Similarly the walled garden was collapsing, and many of the farms were in a poor state with broken fences. Some had not been occupied for a long time. Other correspondence revealed the truth of this and the fact that the wall of the mill had fallen down.”

After purchasing the lease on the estate he set about building a mansion in the latest ‘Moroccan’ fashion with extensive landscaping based on plans drawn up by ‘Capability Brown’ ➚.

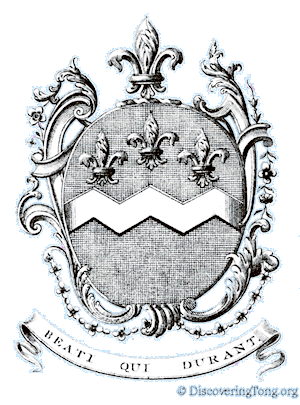

Chapter 4. Beati Qui Durant

The second generation of Durants at Tong in the early nineteenth century epitomised the indolent life of the new class of wealthy families. George Durant II threw himself into the role of a wealthy gentleman with houses in London, Clamart ➚ (France), Childwick ➚ (near St Albans), and Tong (Shropshire).

Chapter 4 unveils the private life of George Durant II with shockingly frank reports of his many illicit affairs: (Beati Qui Durant – The family crest of the Durants is a pun and can be translated as ‘Blessed are they who endure’ or ‘Blessed are the Durants’. The presence of the Fleur de Lys created excitement in France as it is the Royal insignia and in true Durant style this was pure affectation, there is no evidence of any French aristocratic family connections.)

Beati Qui Durany – Crest of the Durants

“The affair, with Elizabeth Cliffe, took place while Mary Bradbury was pregnant. Once, while Mrs Durant was away, he was found in bed with Cliffe in the room opposite the Nursery. The servants were shocked, and pulled him away from her saying that he was ‘always after her’.

This conduct, said the lawyer was “more immoral, more degrading and more disgraceful – making a brothel of his own house…. Scarcely disguising his guilt from his servants.” In the end, Mrs Durant was granted a divorce and alimony of £600 p.a. The solicitor contested the amount of the alimony, and after two years’ negotiations, it was reduced to £400. To celebrate this achievement, George Durant built a monument on Knowl Hill. It was a square building, two stories high, surmounted by pillars 80ft high. A stone over the door was inscribed with the words Optimo Adico TW (TW was the solicitor, who ended up in jail on other offences).”

“George Durant was reputed to have a child in every cottage on the Tong estate. He liked to be godfather to them, and gave them strange names like ‘Napoleon Wedge’, ‘Columbine Cherrington’, ‘Gustavus Adolphus Martin’, ‘Luther Martin’ and ‘Cinderella Greatback’. It is almost as if he saw these children as playthings.”

After a long divorce case and the death of his first wife, he married Marie Celeste Lefèvre who was 25 years younger than himself. He had heated disputes with some of his many children. But he had his more compassionate and paternal side too; he took his responsibility as Lord of Tong seriously:

“They attended Church every Sunday. When in London, he went to Brompton or Kensington Parish Church ➚. Celeste attended a Roman Catholic Church, and had several of her children baptised as Catholics. At Tong, Durant turned the Chantry Chapel into his family pew. The walls were panelled, and it had settees and a fireplace. Halfway through the morning service, a servant came up from the Castle with a donkey carrying Mr Durant’s lunch. The servant carried the tray down through the Church into the Chapel. Every Sunday, after the vicar left, he catechised the children. Each year theywere taken to Shifnal for a Confirmation service. A diary entry for 22nd January 1832 reads: “Mr Robinson (the curate) preached a very good sermon. Fine. Maria rode round the wood and the kitchen garden, I walked by her. We saw Frank on the road by the Convent and heard he was sent back by the Bishop without getting priest’s orders.” ”

Throughout his estate at Tong he built eccentric buildings and monuments, many of which can still be seen today. The book has a number of colour plates showing George Durant’s own sketches of the buildings he designed including ‘The Hermitage’; ‘Convent Lodge’ and ‘Belle Island’ published for the first time. He hired a hermit to live in the grounds of the Castle, following the fashion of the time. But he had squabbles with some of his 20 legitimate and many illegitimate children, as we can read from George Durant’s letter of 1839:

George Durant’s Castle at Tong – garden side view

“‘On the 9th June Ernest and Anguish came into my yard with six dogs and beat my yard dog (a scotch terrier) to death while their mastiffs held him down. They presented to claim access by a road through the yard which has been legally stopped for 26 years. Ernest Durant has married a solicitor’s widow and he is in a cottage adjoining my land where he increasingly has chimney fires and is firing guns by my poolside and insulting members of my family whenever they are in sight. Please to say immediately how to proceed.’

Durant enclosed a set of signed witness statements. One is from George St George; two are from the village constable and a police officer; and the others are by servants. It is clear this was the culmination of a series of events instigated by Ernest and Anguish, asserting their rights to walk through the stable yard. Twice on previous days the village constable had been called to prevent it. But the real causes were deeper. On the 9th June they broke down the fence and came in with six dogs, three servants and a brace of pistols each. The disturbance bought the family out onto the balcony. The party included, George, the second Mrs Durant, their neighbour Mrs Bishton, George St George and Leonard Henry who had just become incumbent…”

The fraught family relations are exemplified by the behaviour of some of his sons on the news of their father’s death:

“That night, the villagers of Tong did not sleep well. As soon as he heard the news, Ernest Durant mounted his horse, and galloped through the village shouting, ‘The old man’s dead at last’. At the suggestion of their late brother George, Ernest and Frank gathered together a number of workmen from the estate. They went up to the offensive monument on the Knoll that their father had erected to his corrupt solicitor. They placed 70 lbs of gunpowder underneath, and blew it up. The explosion shook the Village. Some thought the end of the world had come. The stone, with the offensive inscription, was ground into powder and mixed into a heap of manure. Justice was done at last! ”

Chapter 5. Tong Castle’s Decline and Fall

Tong Castle 1731

Romantic view of Durant castle.

By the mid-nineteenth century the industrial revolution brought further changes to Tong. The Durant money had all but gone and maintaining such a grand mansion as Tong Castle proved costly. George Durant IV sold the estate to the Earl of Bradford in 1854. This extended the Bradford estates ➚ that existed to the north of the parish. The Castle was then rented out to the industrial entrepreneur John Hartley ➚, mayor of Wolverhampton and owner of collieries, ironworks and glassworks. John Hartley was a leading local figure and dubbed the ‘Squire of Tong’. Once again, Tong was following the national trend that replaced ‘colonial’ money with ‘industrial’ money. However funds were insufficient to repair and refurbish the castle.

“Mrs Christabel Werstley (Mrs Hartley’s great grand-daughter) recalled splendid Christmas celebrations. However, all the events took place on the ground floor, because the upper rooms were not safe. At the slightest shower of rain, hip-baths had to be placed all over the building to catch the water, which was pouring through the roof.

When Mrs Hartley died in 1909, it was decided to sell the remaining contents of the Castle. The sale catalogue listed the contents. There were nearly 1,000 items, plus the contents of 25 Bedrooms, and 18 reception rooms. There were still 130 oil paintings, and six carriages. There were 759 books; 161 bottles of wine; musical instruments; crockery; cutlery, and vast amounts of furniture. The sale took place over 3 days at the end of September. Mr Ingram Brown told me that he attended with his father, taking their purchases away in a horse and cart. During the sale, the main staircase fell in.”

One hundred years on and the Castle had become a dangerous ruin. Chapter 5 describes its eventual demise in 1954:

“On the night before the demolition, two girls from the village reported that they had encountered the ghost of a monk leaving the Castle. Then, on 18th July 1954, a large crowd gathered to watch this historic event (illustration page 71 of the book). The operation was conducted by the 213 Field Squadron Royal Engineers (T.A.). 208 boreholes were placed around the building, using 136 lbs of plastic explosive, and 75lbs of amatol. The Church windows were opened to cope with the blast. At 2.30 p.m. Lord Newport fired the charges. There are some fine photographs of this event, with the whole base of the Castle covered in smoke. A great cloud of dust and debris covered most of the buildings in the village. Tong Castle was no more. Among the people attending was Anthony Durant (later the M.P. for Reading). It was an event that the first and second George Durants could not have imagined.”

The Castle’s secrets did not have to wait long before they were uncovered. Alan Wharton carried out a rescue archaeological dig in 1976-1980 to better understand its nine centuries of history. The M54 now cuts a path directly through the middle of the site of the castle, small portions of the remains can be seen on either side of the motorway.

For more about the nine distinct buildings on the Tong Castle site unearthed by Alan Wharton please visit our Castle Excavation pages.

Ecclesiastical Tong

Chapter 6. Tong College

Brass of Sir Arthur Vernon in the Vernon Chantry.

If you have visited medieval cathedrals you will often find a monastic style building ➚ adjoining it. As well as serving the church, the chaplains of the college served the local community. Tong, Shropshire was one of the relatively few collegiate churches ➚ that was established in the fifteenth century.

“The massive increase in sudden deaths led to a great desire to pray for the dead. The Battle of Shrewsbury ➚ in 1403 led to the establishment of Battlefield College, with 8 clergy to pray for the souls of those, who died in that massive slaughter. There were different sorts of Colleges; some provided singers for cathedrals; some were attached to hospitals; some included academic institutions; and others (like Tong) were Chantries. Part of this was a reaction against Monasteries; the monasteries had developed great wealth, and people became suspicious of their increasing power. So the rich became more inclined to endow their own Colleges and Chantries, to pray for the dead and to provide education for the community.”

Tong College, a victim of Henry VIII’s dissolution in 1546, provided Tong with tuition, pastoral and heath care as well as a source of employment. Chapter 6 documents the busy lives of the chaplains at the college.

“Payment was made for work done. The Parochial Chaplain and the Schoolmaster received additional payments. Those, who failed to attend services, were fined halfpence a time. The College building must have been quite big; meals were eaten in a common refectory. All talk had to be in a subdued tone. The door was locked at night, and the Warden kept the key. A Steward or Cellarer was appointed to deal with provisions. There are rules for entertaining visitors: ‘The brothers are to abstain, as far as they can, from the introduction of strangers that the ground of distraction may be cut away as much as can be done honourably.’”

Ground plan of the college drawn in 1911 based on

parch marks in the field to the south of the Church.

The college was supported financially by endowments of land, which were located locally in Lapley and Wheaton Aston, but also further afield in Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire. The college clearly prospered:

“The accounts for 1437 and 1440 reveal that the College was employing five farm servants. By this time, it was providing enough corn, meat, and dairy products to meet all the requirements of the community. In 1438, the College was able to sell surplus rye and wool. In 1432, they had 92 sheep and 30 stones of wool were sold. By 1441, the amount of wool went up to 39 stones. There was a vineyard situated to the south east of the College.

A group of five or six clergy at Tong would not have been unusual at this time. In 1500, the population of England was 2 million, and there were 23,500 clergy. Every resident in Tong would have been, in some way, connected to the Castle and the College. So here was a compact, and self sufficient community. ”

On the dissolution ➚ of Tong College in 1546 the building and its lands passed to Richard Vernon and James Woolriche before passing on to William Pierrepont with the rest of the Tong Estate.

Th College served as almshouses for a while before it was demolished by George Durant as part of his landscaping in 1765. Alan Wharton excavated the college in 1981. It lies in the field to the south of the Church just clippedby the A41 bypass of Tong village.

For information about the excavation carried out on the Tong College site, please visit our Excavation pages. See also : Tong College plan

Chapter 7. Tong Church

The history of an English village is often brought to life by studying the church.

The present Tong Church and College were founded by Dame Isabel Pembrugge with the existing church and college at Shottesbrooke Berkshire ➚ in mind as the model. There is evidence of an earlier Norman stone church at Tong, and the present church includes a fragment of an early tomb in its north wall. The current Church building of 1406 has only been amended for the housing of the Great Bell and the addition of the Vernon Chantry in 1510. The Victorian restoration of 1892 was carried out sensitively, restoring rather than rebuilding.

St. Mary and St. Bartholomew’s Church, Tong

“There are many descriptions of Tong Church. The earlier ones help us to see what happened at the Victorian restoration. Archdeacon Cranage wrote his description, just after its restoration. He describes it as ‘a most interesting building’ of ‘perpendicular character’, and admires the restoration work. There is an octagonal central Tower, and within it rises the central spire altered by Sir Henry Vernon, so that it could contain the Great Bell of Tong. Above it, are six bells, and a Sanctus Bell. The bells are rung from the middle of the church. Ringing is not easy, because the floor slopes from the east to the west end. The slope may be due to the bedrock, but some have thought it was constructed to enable the Church to be cleaned easily. Water poured out at the East end would automatically run to the West.”

Chapter 7 takes us on a tour of the church describing many of its unique features. For example concerning the fine, original carved stalls in the chancel :

“The return stall seat, for the College Warden, has an Annunciation scene with a lily in the centre with a crucifix emerging from it. This design reflects a long tradition that Jesus’ crucifixion took place on the anniversary of the Annunciation. This demonstrates that Mary and Jesus share a common suffering. There are very few depictions left since the Reformation and Tong is unique in being on a misericord.

“The fifth stall on the south side is of special interest. This is the only stall, with carving rather than decoration, at the top. On the right hand side is an angel, holding a shield on which are signs of the passion. This represents a typical form of devotion of the time. On the left is a face, (possibly a ‘Veronica’) which is very like the one on the Turin Shroud. Beneath both is an heraldic bird. The bird is that of the de Weston crest, which can be seen in the neighbouring Church at Weston-under-Lizard. In that Church are two tombs of de Westons. They were crusaders, and members of the Knights Templar ➚. At one time, the Knights Templar claimed to posses the Turin Shroud ➚, and they had a devotion to the face of Christ. On the seat below is the carving of a Green Man ➚. So the whole stall becomes a meditation on faces.”

The tomb of the foundress Isabel Pembrugge is associated with a local custom. On Midsummer’s Day roses are placed on her tomb. The custom ➚ dates as far back as 1200 when the flowers were placed by an image of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

“So a custom over 200 years old, continued into the new church. But at the Reformation, the statue of Our Lady would have been removed, and so the roses came to the other lady, who was lying near the Lady Chapel. The custom still continues today. Such customs were common practice. In 1316, John de Tong was granted land by Robert de Prees; the rent was a rose on Midsummer’s Day. In 1353 there was a grant by John Byschop of 3 pieces of land at Tong Norton, with a similar arrangement. Another grant was conditional on the exchange of three arrows with goose feathers.”

Tong Church has splendid monuments to six generations of the Vernon family, including the remarkable Chantry (or ‘Golden’) Chapel.

“The whole Chantry is remarkable with its fan vaulting ceiling, which was originally painted in green, red and gold. The vaulting is very like that in the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey. The size of the Tong Chapel is much smaller, what could be achieved is restricted. It is the only surviving piece of medieval fan vaulting in Shropshire. On the east wall are the remains of a rood painting. Some of the colour is still quite bright. Underneath is an inscription requesting prayers for Henry Vernon and his family. On the west wall, there is a hollow bust of Arthur Vernon, depicted in a pulpit, preaching. On the floor is a fine brass of Arthur Vernon dressed as an Oxford M.A. Arthur was Henry’s third son, tutor to Prince Arthur and subsequently Rector of Whitchurch.”

There are also memorials to the Stanleys, Anne Wylde, Henry Willoughby, William Skeffington, Elizabeth Pierrepont, Charles Buckeridge, Daniel Higgs and the Durants. All these are described in the book.

In the churchyard there are notable memorials to the Reid Walkers, the Hartleys, the Chrysom’s churchyard and more of the Durants. Details of the Victorian restoration describes some worrying actions which would now be considered tantamount to vandalism:

“The Victorians thought that mediaeval churches were meant to have stone walls. They were not. The mention of colour on the wall is disturbing, and it hints that there may have been murals of some sort. Griffiths says that there was a small patch of an ancient mural.”

For an online tour of Tong church please visit this page.

The monument to Anne Wylde in the Chancel

Chapter 8. The Treasures of Tong

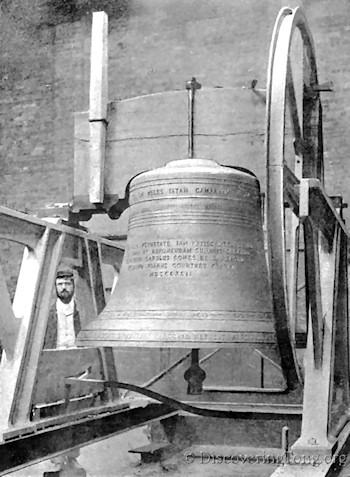

The Great Bell of Tong

Most villages have accumulated a few objects of interest and value over the centuries. Tong has more than its fair share, Chapter 8 describes them. Tong boasts a Great Bell installed by order of Sir Henry Vernon – the largest in Shropshire taking three people to toll it. After damage in the Civil War and again in 1848 it was last recast at the time of the church restoration in 1892. There are rules restricting when it can be tolled.

“The booming of the Great Bell echoes all over the village. Thus it tells part of the Village story. To this day, a member of the Vernon family, or of the Royal Family does visit occasionally. The tolling of the Bell is a sign of continuity, over five centuries.”

The belfry also has a peal of six bells and a Sanctus bell. In the Chancel is a rare Easter Sepulchre ➚. The vestry used to house a large ‘Minister’s Library’ founded at the end of the seventeenth century and at one time containing 409 rare and valuable books.

“When the Duke built the Vicarage, the Library was moved from the Castle. But because of absentee Vicars, it was moved into the Church Vestry and a fireplace installed. George Durant (II), and the Revd T. Buckeridge, added some other books. During the 1892 restoration the Vicar checked the volumes against Botfield’s Catalogue. He discovered that it contained 409 books, of which 89 were missing. There were 70 books not included in the Catalogue. Having found some volumes from the Library in a second-hand book cart in Wolverhampton, Auden did a further check. Clearly pilfering was rife.”

Dame Elinor Harries donated a number of treasures: a pulpit fall; the pulpit itself; a silver ewer but most significantly the Tong Cup. The Tong Cup was originally ascribed to the workmanship of Holbein – made in silver gilt holding a rock crystal ‘cup’. It is now attributed to Dierick Lookermans from about 1611. It has always been greatly admired and now takes pride of place in the Treasury of Lichfield Cathedral ➚. See also: Tong Cup.

“There is a crack in the crystal. This was caused by the Vicar of Donnington, who dropped it on the floor, when he was shown it by his fellow incumbent. The same notebook, which describes that incident, also records that, following a family baptism from Weston Park, the Earl of Bradford asked to borrow the Cup, in order to show it to his friends and relatives. The notebook continues ‘Thirty years later the Vicar of Tong went up to Weston Park with his son to demand it back’.”

The author of this book, Robert Jeffery

holding the Tong Cup.

Chapter 9. Of Clerics and Clerks

The clergy offer more than just pastoral care of a parish, they were often the eyes and ears of the Lord of the Manor who until quite recently appointed them. Many were not resident in the village, their work being carried out by curates that the parson appointed. For many years attendance at church was compulsory, for it was as a condition of the tenancy agreement, with a fine payable for non-attendance.

Chapter 9 documents the lives of all the known priests of Tong Church and also what is known of the Parish Clerks who often acted as the link between the parson and the community. The earliest well documented appointed priests are from the period of the Civil War and had a difficult time:

George Boden, notable Parish

Clerk who promoted the Lttle Nell story.

“Robert Hilton was Vicar of Lapley in 1638, but he was ejected from there in 1647. William Pierrepont appointed him to Tong in 1650. This was an act of kindness in those troubled times. Hilton ran a school at Tong. His successor at Lapley (who was removed in 1660) complained that “he did not get his arrears from 1647-9”. (This relates to glebe income, or fees). He also complained that he had an order to pay Mrs Hilton, (even though her husband was Vicar of Tong) and that it was unfair that Hilton also held the Sutton (Stretton) Chapelry, in Staffordshire. In 1660 Hilton was re-instated at Lapley. These events demonstrate the way some clergy tried to survive, during the Commonwealth period. Many depended on kind patrons to help them out.”

George Rivett-Carnac was one of the more colourful incumbents as he was a famous sportsman:

“George Rivett-Carnac was educated at Harrow School, Cambridge, and Chichester Theological College. He was a considerable sportsman. He played ice hockey, and cricket. On one occasion in 1875, playing for Priory Park against the South of England, he bowled out W. G. Grace for 0, and his brother G. F. Grace for 2 in the same over. He served curacies in Norfolk and Kew, and was at Tong for eight years (1882-90). He had two subsequent livings. He inherited a Baronetcy in 1898, and died in 1932. He was married to the granddaughter of the rural poet, George Crabbe.”

Of the parish clerks Robert Jeffery reports one incident concerning William Woolley a member of the local family of clockmakers:

“A little later, William Woolley was Parish Clerk. He was also a clockmaker, and lived at Tong Hill. Woolley was dismissed from his post, after a visiting preacher complained that there was no mirror in the vestry. Woolley called him ‘a confounded cockscomb’. George Durant (II) subsequently provided a mirror.”

Chapter 10. Living in Tong

Embroidery of the main building in Tong made by Anne Tuck.

In an old village like Tong, Shropshire all the houses tell a story. Knowing about the Church and Castle does not give much of a clue to life of ordinary village folk.

Tong has rich agricultural land and many of the buildings reflect this, it had over a dozen farms. Looking back before the days of modern transportation the village was much more self-contained with its own carpenters; wheelwrights; millers and publicans (it once had four pubs). Tong had an iron forge driven by water power and cottage industries including clock-making and shoemaking. Tong is only eight miles from the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution ➚ on the River Severn.

“The Tong Clock-makers were established alongside the Forge. The most notable of these was John Baddeley. He was baptised in Tong Church in 1720. His father was a blacksmith. When he was 18, he decided to become a clock and watchmaker. He studied mechanics, and, in 1762, began working on optics, and he constructed a reflective telescope. Later, he moved to Albrighton, and is buried there. Shaw’s Staffordshire comments on him: ‘His superiority as a clock maker will be told for some years to come by the numerous domestic and turret clocks substantially constructed by him in every part of the country within many miles of Albrighton where he long resided.’ He made the clock for Tong Church. It was in use until 1984; the mechanism is on display in the Church.” See Tong Clock

Chapter 10 of the book takes us on a tour of the parish visiting each significant house including: Kilsall Hall; Convent Lodge; Tong Park Farm; Tong Hall; Tong House; Almshouses; Red House; Old Post Office; Church Farm (the former village pub); Old School; The Priory; Tong Hill Farm; and Hubbal Grange Farm. At the satellite village of Tong Norton is Bell Inn Farm; Norton Farm; Old Bush House; Knoll Farm; Norton Mere. Towards Brewood along the Offoxey Road stands Offoxey Farm; Holt Farm; Meashill Farm; White Oak Farm and White Oak Lodge;

White Oak was the scene for a boxing match :

“In 1828 a prize-fight took place there, between F. Samson of Birmingham and ‘Big Brown’ of Bridgnorth. The prize was £500, and the fight lasted for 42 rounds. The two men had fought each other before, but this time Brown fixed the fight. He ruined his backers, many of who had pawned their beds to support him. The Shropshire Quarter Sessions dealt with serious offences during this fight, and commented that such events were: ‘destructive of the public peace and injurious to the property and endangering the lives of individuals in the parishes of Tong and Albrighton’.”

Hubbal Grange was the setting when Charles II ➚ came close to capture by the Parliamentarians in 1651. The famous Royal Oak ➚ is only yard’s from the parish boundary at Boscobel.

“After the battle of Worcester Charles fled to Whiteladies, where, with Richard Penderell, they planned a failed escape, via Madeley into Wales. After the Restoration, the Penderells received a Royal annuity. In order to disguise the King, William Penderell cut off his hair. He kept the hair, and sold bits, to supplement his income. George Durant (II) demolished the main part of Hubbal Grange and built a smaller house, which is now within Tong Park Farm. Even in 1933 there were stories around that Hubbal was where Charles had hidden himself. Robinson quotes a Mr Kingston: ‘It is a much restored cottage standing in the midst of fields, lonely and difficult to approach… A comparatively modern oven was pointed out as being the place where Charles hid himself. We objected that a good sized man ‘more than two yards high’ could scarcely get into so small a space but the good wife overruled our objection declaring that ‘there’s no knowing what you would do if they were after you.’”

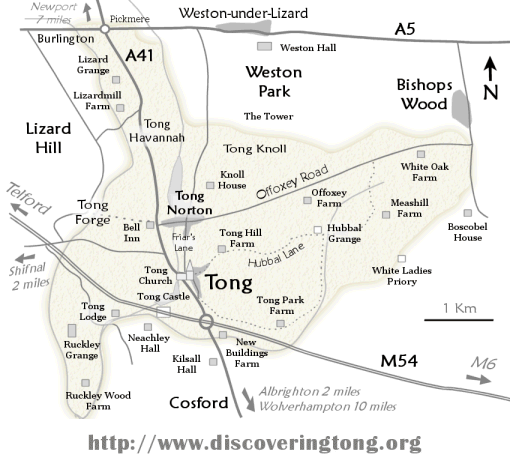

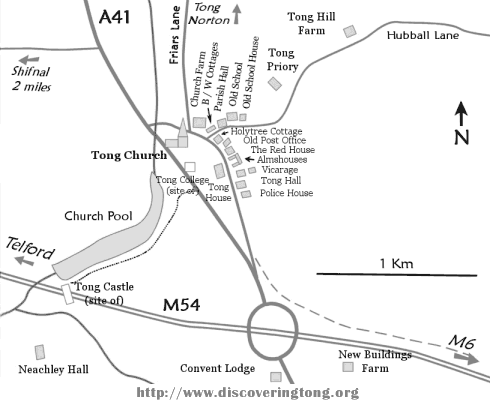

Map of the centre of the Village of Tong

On the west side of the village is Vauxhall Farm; Ruckley; Tong Forge; Lizard Grange and Lizard Mill Farm; Tong Havannah and Burlington.

The Ruckley estate was owned in by John Reid-Walker in the early twentieth century.

“In 1896, the owner was John Reid Walker, who rebuilt the house. Whenever he travelled to Tong by train, after it had left Cosford, he used to pull the communication cord. He then handed to the guard his fine, and walked the few yards to his house.”

Chapter 11. Scenes from Village Life

The lives of the villagers of Tong are not normally recorded alongside the Lord of the Manor and yet in the case of Tong there are glimpses of life in a close-knit village community.

Chapter 11 lists some of the village clubs and societies and documents special occasions – such as visits by the Lord of the Manor. The village school was a point of focus and we read how schooling changed over the years:

“The school logbooks give an insight into school and community life. Very often the school was closed, because of fever in the area. Attendance was never more than 70% per child. The reason for this was a mixture, caused by potato picking, helping on farms, or simply playing truant. One child was expelled for an unmentionable deed. Some entries reveal the teacher’s anxieties. An entry in 1893 reads: ‘Harry Wedge swallowed a pin. It would be a help if teachers were told what to do on these occasions’.”

A villager took note of some of the schoolboy pranks that were played. In 1950 a historical drama ‘The Spirit of Tong’ was devised by Revd E. J. Gargery setting out the story of the village. By this time myth had become intertwined with historical fact.

“The characters, which are encountered, include Dame Isabella, the Vernons, through to King Charles and Little Nell. Some of the old legends are perpetuated. The character of Dame Elinor Harries speaks of the Tong Cup as a Ciborium. ‘which had come from Holbein’s day to mine’ and she says ‘I did bestow a vestment worked with skill And loving care; And by Cistercian Sisters, long ago, Embroidered well.’ So the false stories, about the Tong Cup and the pulpit fall as a vestment, are perpetuated.”

Tong was awarded a Royal Charter in 1421 to hold an annual fair – the ‘Tong Wake’ by Henry III to mark St. Bartholomew’s Day.

“Probably some of these games related to different times of year. But the main social event was the Tong Wake. King Henry III, had granted this feast to Tong in 1421, along with a weekly Thursday market. Both events were to be held in the grounds of Tong Manor. The wake was meant to be held on St Bartholomew’s Day (24th August), but was transferred to St Matthew’s Day (21st September), to ensure the completion of the Harvest. The Wake lasted several days, and involved lots of sports, races and games. These included chasing a pig or a sheep with a greased tail, climbing a greasy pole, and eating treacle buns. The women’s races had gowns as prizes. A week before the Wake, everybody would be cooking, and baking pies, puddings, and joints of meat. There were barrels of beer, and much jollity.”

Literary Tong

Chapter 12. The Shakespeare Connection

The effigy of Sir Thomas Stanley, the inscriptions run along the

base of the tomb.

William Shakespeare ➚ is such a domineering figure in English literature that any village that has a connection with him will receive the interest of a host of scholars seeking out the man behind the plays. In the last few years fresh insights into the great playwright have associated him with leading Catholic families at the time of the emergence of the Protestant supremacy. At Tong one of the most elusive connections to Shakespeare has been known to exist for some centuries. In this chapter the author unravels the host of theories concerning Shakespeare and Sir Thomas Stanley’s tomb in Tong Church.

“In 1929, a Mrs Esdaile wrote a pamphlet entitled Shakespeare’s verses in Tong Church. She asserted the authenticity of Shakespeare’s verses. She pointed out that doggerel rhymes, like those on Shakespeare’s own memorial in Stratford-on-Avon Church, were written because they were easy for the stone carvers. She mentioned the Shakespeare connection with the Stanleys. A Midsummer Night’s Dream was written for the wedding of Ferdinando (fifth Earl of Derby ➚) in 1588. Ferdinando had taken over the patronage of Shakespeare’s company of players in that year.”

The connection between of William Shakespeare and Sir Edward Stanley is not open to debate. It is also well known that Shakespeare’s patron the Earl of Southampton ➚‘s wife was a Vernon to whom the Stanleys are closely related.

In his summing up using all the latest sources and scholarship Robert Jeffery unravels the common myths that have sprung up on this topic.

“The Stanley tomb has also attracted the attention of those who wish to undermine Shakespeare as the author of the plays. One theory ascribes them to William, Earl of Derby ➚, arguing that he wrote the words on this tomb in 1632. The evidence above undermines this and other theories.

“Ask who lyes here but do not weep

He is not dead he doth but sleep

This stoney register is for his bones

His fame is more perpetual than these stones

And his own goodness with himself being gone

Shall lyve when earthlie monument is none.

Not monumental stone preserves our Fame

Nor sky aspiring pyramids our name

The memory of Him for whom this stands

Shall out live marble and defacers’ hands

When all to tyme’s consumption shall be geaven

Standley for whom this stands shall stand in Heaven”

The lines attributed to Shakespeare on the Stanley tomb at Tong Church.

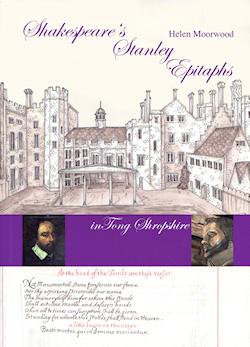

Shakespeare’s Stanley Epitaphs in Tong, Shropshire

A book about the verses on the tomb of Sir Thomas & Sir Edward Stanley in St Bartholomew’s Church Tong, with their first ever biographies. By Helen Moorwood, published by RJL Smith and Associates, Much Wenlock.

This book plays the role of ‘prequel’ to a re-investigation of the ‘Lancastrian Shakespeare’ theory, which claims that young William Shakespeare spent some time in Lancashire with the Catholic Hoghtons and Heskeths. One family that has now emerged as crucial in explaining Shakespeare’s ancestry and early biography, including his spell in Lancashire, is the Stanley Family, Earls of Derby, ‘Kings of Lancashire’ and Lords of Man. Sir Edward Stanley, the ‘hero’ of this book, born in Lancashire, was a grandson of Edward 3rd, a nephew of Henry 4th and first cousin of brothers Ferdinando 5th and William 6th Earls of Derby.

Sir Edward received in 1601-3 from his friend William Shakespeare two Verse Epitaphs for his family tomb in Tong, Shropshire. These are the only ones still to be seen today except for the one on the Bard’s own gravestone. Sir Edward, through his Stanley cousins, his Vernon mother and his Percy wife, happened to be rather closely related to three Earl Alternative Authorship Candidates, several characters in Shakespeare’s Lancastrian History Plays and several candidates for the ‘Dark Lady’ of the Sonnets. Sir Edward can thus be seen as a pivotal figure in the Shakespeare-Stanley constellation. This book concludes with the first ever biographies of of him and his father Sir Thomas Stanley, who suffered for planning to help Mary, Queen of Scots escape from Chatsworth in 1570.

This book includes 29 Chapters, 12 Appendices, an 8-page colour block and 99 black and white illustrations, and a comprehensive Bibliography and Index.

172 mm x 240 mm, 472 pages, ISBN: 978-0-9573492-2-3

To order a copy please visit : http://moorwood.de ➚

Chapter 12 also covers some other intriguing literary associations including John Milton ➚; Lady Venetia Stanley ➚; John Evelyn ➚ (the diarist) and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu ➚.

Chapter 13. Some Victorian Curiosities

In the last chapter of the book, the author shows how Tong influenced the literary works of Harrison Ainsworth ➚; Charles Dickens; Ellen Thorneycroft Fowler and P.G. Wodehouse.

The flight of the future King Charles II after the rout at the Battle of Worcester ➚ in 1651 was turned into an adventure story by ‘popular historian’ Harrison Ainsworth. The King passed through Tong (Hubbal Grange) and hid in the Royal Oak ➚ in neighbouring Boscobel.

“Ainsworth is no longer a significant literary figure, but the effect of his book was to bring the events taking place around Tong and Boscobel into public consciousness, and to attract visitors to the area.”

Indeed a trip to Tong on the new railway became a popular weekend outing for people working in Wolverhampton and beyond.

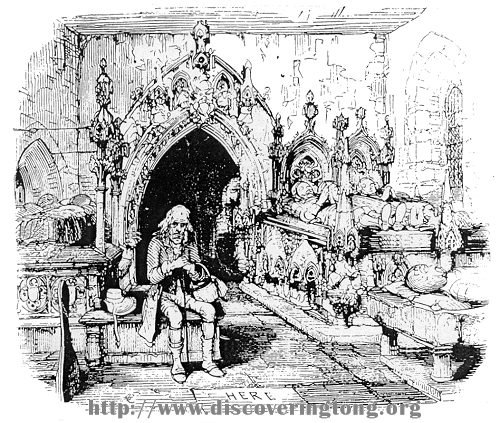

Cattermole illustration for Charles Dicken’s ‘Old Curiosity Shop’ with Tong Church in mind. Little Nell’s grandfather grieves beside her grave.

To boast links with William Shakespeare would seem quite enough for a small village, but Tong can rightly claim links to a great Victorian writer too.Charles Dickens ➚ is believed to have set the famous scenes of one of his most successful books ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ at Tong. It was this link that generated a new cottage industry at Tong and a number of new stories came to be made. The serialization of the book generated huge popular interest in Little Nell and her grandfather as the story unfolded week by week.

The Old Curiosity Shop caused a sensation when it was published just as would happen today when a serialised TV drama reaches a climax.

“Dickens readers were drowned in a wave of grief no less overwhelming than his own. When Mcready returning home from the theatre, saw the print of the child lying dead by the window with strips of holly on her breast, a dead chill ran through his blood. ‘I have never read printed words that gave me so much pain’, he noted in his diary, ‘I could not weep for some time. Sensations, sufferings have returned to me, that are terrible to awaken…’ Daniel O’Connell, the Irish MP, reading the book in a railway carriage, burst into tears, groaned ‘He should not have killed her’, and despairingly threw the volume out of the train window. Thomas Carlyle, previously inclined to be a bit patronising about Dickens, was utterly overcome. Waiting crowds at a New York Pier shouted to an incoming vessel, ‘Is Little Nell dead?’…”

Dickens undoubtedly did know about Tong:

“There is another connection. Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth, in 1812. His grandmother was Elizabeth Ball. She was the daughter of James and Amy Ball, of Claverley in Shropshire. She was baptised there, on January 10, 1746. Before she married, she was housekeeper at Tong Castle. She married William Dickens in 1781 when she was 36, so she may have been at Tong for some time.”

The description of the Church in the ‘Old Curiosity Shop’ is unflattering: ‘A very Aged, Ghostly Place’ but matches the state of the affairs prior to the Restoration of 1892 with only a little exaggeration for dramatic effect. Despite some scholars attempts to undermine the theory, there is little doubt that the closing scenes of the death of Little Nell and her grief-stricken grandfather were set with Tong in mind.

However the influx of visitors to see Dickens’ Tong proved a valuable line of income for George Boden (the parish clerk) much to the annoyance of John Auden (the vicar). The tale had by then become embroidered with all sorts of errors, and there is still a place in the graveyard that has a plaque claiming it as ‘The reputed grave of Little Nell’. Chapter 13 sets out the vicar’s view on the matter.

“He denied that he encouraged this tradition. Boden persisted, in spite of the objections. Postcards were sold of Little Nell’s House: and also china plates, cups, and teapots were produced. They depicted Little Nell and her grandfather. There was indeed money in it. George Boden could tell a good yarn. One person remembers coming to Tong when she was aged 8, and being so moved by his heart-rending story, she cried all night. In 1933 George Boden told his yarn to the Wolverhampton Express and Star and the reporter believed it. It is an amazing fabrication.”

Epilogue

There are eight Appendices covering a variety of topics:

The Owners of Tong Castle;

Some further notes on the Durant Family;

Valuation of Tong Estate 1763;

List of Wardens of Tong College;

List of Parochial Clergy;

List of Tong School teachers;

List of guide Books to Tong Church;

Notes on the National Census Figures 1801-1901.

Followed by a comprehensive Bibliography and Index.

In the Epilogue Robert Jeffery brings together his astute observations on how the local history of the village of Tong in Shropshire typifies the concept of a unique ‘place’ and how stories have grown and evolved over the centuries.

“Less easy to define is the way a community is given identity by the way people experience it and talk about it. Tong Village is a distinctive entity, the outlying areas less so. A good view, a fine building, trees and vegetation can lift our hearts or as Tony Hiss puts it:

‘Particular places around us, if we’re wide open to perceive them, they can sometimes give us a mental life.’

But there must be that willingness to see it. Through it comes the understating that our environment is actually life sustaining. We need a place where we can be. Where we live also conditions what we do and what sort of people we become. This would have been particularly the case in an enclosed feudal environment, but in so far as people can choose where they live, they both mould and are moulded their surroundings. Winifred Gallagher calls this “psychological ecology” she quotes the work of Roger Barker looking at people’s behaviour:

‘The more he watched all sorts of people go about their business in shops, playing fields, offices, churches, and bars, the more certain he became that individuals and their inanimate surroundings together create systems of a higher order that take on a life of their own.’

This can lead people to be very keen to maintain things the way they are, and only take to change slowly. This goes some way to explain why people stick to myths and legends. The story has, in some way, become part of their identity.

It is this matter of story, which seems to dominate over all other aspects of what makes up a community. The storytellers sustain it. Every person, every building, has its own story and together they make up the story of the community. The stories are passed on. They are altered and enriched in the telling. Some stories are forgotten. Some are rediscovered. Those who have examined the nature of story, point out that there are only a certain number of basic stories and many of them (like The Old Curiosity Shop) involve a journey. Many are essentially the biography of a person or a place. Tong tells its own ongoing autobiography. ”

Parish Admin:

Treasurer:

Tong Church Wardens:

Wendy Aykroyd, Tel: 01952 291532

Email: admin@shifnalbenefice.org.uk

Michael Pilsbury. Tel: 01902 750382 or Email: mickpilsbury@sky.com

Sandy Baker, Tel: 01902 754024 or

Email: Sbbaker10@hotmail.com

Robert Kerrigan, Tel: 07825 683399 or Email: robertkerrigan@btinternet.com

Tong Tours:

Tong Tours are booked through Wendy Aykroyd, Parish Administrator

Tel No – 01952 291532

Email – admin@shifnalbenefice.org.uk

Baptisms and Weddings:

For bookings of Baptisms and Weddings at St. Bartholomew’s, Tong, please contact the Administrator Wendy Aykroyd in working hours

Funerals:

For funerals please contact Wendy Aykroyd (contact details above) to make sure the church and appropriate member of the clergy is available. She also has the up-to-date list of fees.

Tong Church has everything

But don’t take our word for it. Join us on a tour of our beautiful church….

We are able to offer a conducted tour of our famous, beautiful church. This ancient building was dedicated in 1410, and is held to be one of the finest examples of a church built in perpendicular style in the country.

Our tour lasts for about an hour, during which time you will see the famous Golden Chapel, our unique collection of magnificent medieval tombs and carved effigies. You can explore our historical links with Charles Dickens, William Shakespeare and not forgetting little Nell!

And, not for the faint hearted, try a tour of the tower. You will see one of the largest bells in the country! Nowadays, due to Health and Safety concerns regarding the very worn spiral steps and extremely limited space we only let visitors up the tower at their own risk and make them sign a disclaimer, but Bell ringing enthusiasts are often still keen to visit.